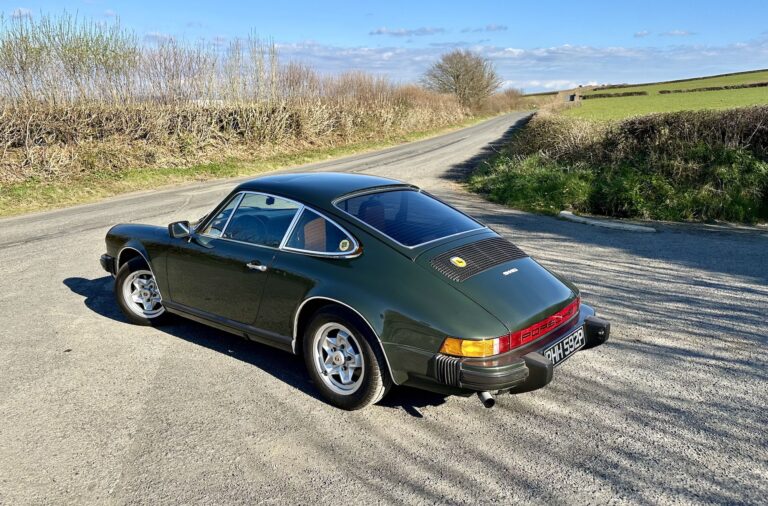

How to check a Porsche 911 for corrosion

There's a problem no car is immune to, even the venerable 911: rust. Wrightune's Chris Wright tells 9WERKS where to check for it, and how to avoid it…

The body of a 911 is steel, and to avoid corrosion, Porsche started using galvanised metal for the shell in the 1970 D-series model, utilising it for the underbody. In 1976 Porsche progressed to using it on the full shell, bar the roof, then finally the whole vehicle in 1977. That zinc coating doesn’t mean it won’t rust though, it just means it withstands water exposure for longer, before it corrodes.

“As a general rule”, explains Wrightune‘s Chris, “For the earlier cars – up to, say, 964 – corrosion on the shell can be a problem. Later cars – 993 onwards – they’re pretty much sorted so don’t have the same issues, but you have to be wary”. The shells of 911s are a fairly open structure, meaning the body joints in the wheel arches, particularly, are exposed to road spray in use.

Categories

That means water, under pressure, is forced into all areas as the car is driven. Given time, that water deposits dirt, or road salt, which builds in the crevices of the underbody, basically forming a corrosion-hastening sponge. Next time it gets wet, it stays wet for longer, giving more favourable conditions for rust to begin.

That is a very crude explanation of the problem, but in essence, that’s how it starts. If you want to check your 911, or especially a potential purchase, how do you go about it, and where do you look? “It is hard to check properly without a ramp, but you want to look under the car, and check everywhere” says Chris. That means into rear arches, kidney bowls, sills, inner wings, and footwells, the corners of all which can all corrode, sometime with unbelievable willingness, so check carefully on an air-cooled car. The top of the car isn’t immune, either. “Screen corners can corrode, as can sunroofs, battery trays, fuel tanks and panel joints” says Chris. Rear wings can hole just aft of the rear wheels, and need catching quickly, if so.

“The problem is, what you can see will only be the tip of it” reveals Chris. “Usually once you strip something, the job escalates quickly. People think you can just patch a repair, but to repair it properly can mean a whole panel has to be replaced” he says. In the case of something like a rear wing, that means not just removing a panel, and making good what you then discover underneath, but also tying an outer repair panel into not just the engine bay corner, but also the roof, sill and two windows. It is skilled work, taking a great deal of time. Repairing just one corner of a car is seldom worth it, as all you do is chase the issue for a number of other years, as the secondary rust then appears in the corner you neglected.

The good news is that later cars, broadly post-993, fare much better with corrosion. “Unless they’ve had body repair through accidents, they generally don’t rust,” says Chris. “A 993 can have issues with screen corrosion, through either glass bonding agents reacting and corroding, or careless fitters scraping mounting faces and not painting them before replacing the screen, but otherwise, they are pretty sorted. That isn’t to say you’d have to keep an eye on exposed body faces for stone chip damage. If I owned a 996, I’d be periodically checking wheel arch lips, or the leading edge of the sill for chips, for instance, but otherwise, serious corrosion rarely takes hold.”

That’s body corrosion, but what of the rest of the car? It’s not immune, sadly. “A guide is that pre-996, the body corrodes, but the mechanicals largely stay in good condition,” Chris says. “Conversely, post-996, bodies stay good, but the mechanicals can corrode”. That manifests in corrosion on brake discs and brake lines of 996s, particularly from lack of use or poor storage. Coolant pipes, condensers or radiators can also corrode, the latter due to leaves collecting in radiators and, you guessed it, holding water over time. Early car fuel tanks can corrode, as can heat exchangers, bumpers and exhausts, but so can torsion tubes, or suspension mounts in extreme cases.

So how can you protect your classic car from rust? ”If it is already rusting, then it is too late to protect,” states Wright, who says don’t just spray something over the top. “Best is to regularly inspect the car, consider some corrosion protection, and catch any corrosion early, if you do spot it,” he says. “Road salt in winter can cause immense damage if you just drive the car, then store it badly,” he adds. “Consider not using it in heavy salt conditions, and if you do, wash the underside thoroughly after use – but dry it equally thoroughly afterwards. Brake disc inner faces on Porsches can corrode quickly on cars that don’t move about, but water left in sill joints or body drains also causes problems.”

As ever, the best way to prevent issues involves paying regular attention to your 911. In reality, keeping it clean means it takes less time to return it to that condition, and it only takes a few minutes to cast your eye around the car, looking in the telltale areas for the start of a problem. Likewise, if you’re buying a 911, Chris suggests a professional inspection is worthwhile, or at least a through check of all the potential trouble spots for ultimate peace of mind.

Contact chris@wrightune.co.uk

01491 826911